Pipestone National Monument History

Pipestone National Monument is a storied landscape!

PARTS OF THIS INFORMATION SOURCED FROM THE NATIONAL PARK WEBSITE AND OTHER SITES

Numerous tribes around the country have oral traditions connecting them to this site, Euro-Americans have been visiting and writing about it since the 1600s, and archeologists have found evidence for over 3,000 years of human activity here and some evidence going back 4,000 years. Today, Pipestone National Monument is officially affiliated with 23 tribal nations and Indigenous people from across the country keep ancient quarrying traditions alive to this day.

-----

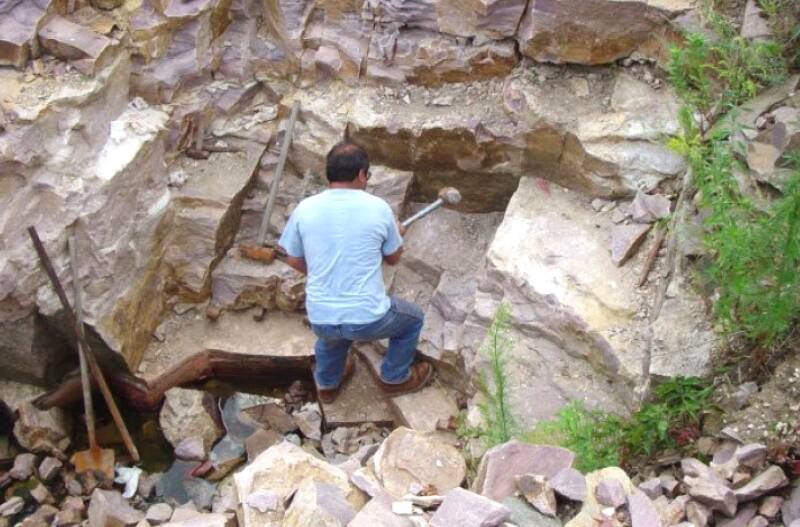

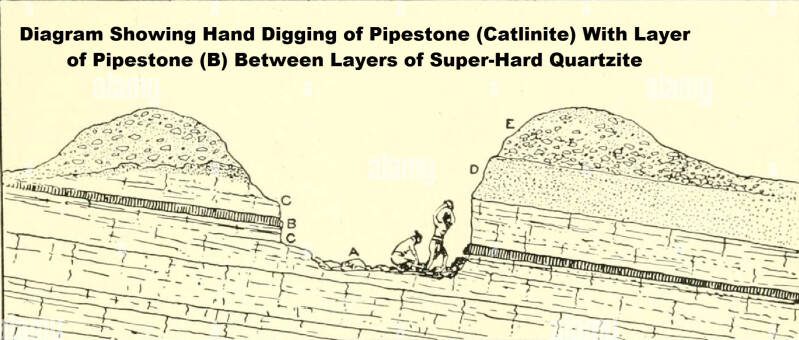

For many centuries, pipestone has been an item of ceremonial importance as well as an object of trade for the tribal groups of the Great Plains. The actual quarrying of this stone is often an unappreciated part of the tradition surrounding pipestone and pipestone crafts. The task of extracting pipestone from the earth is a very difficult one and the hand tools used today are not much more advanced than the tools and methods used in centuries past. The quarrying process is a slow one, and the long, hard hours put in by those who extract the stone often go unnoticed. Quarrying is the first and most basic step of the pipestone tradition. The beautiful pipestone crafts that many of us see are merely the final result of a long process that begins with the monumental effort and the unyielding dedication of the pipestone quarriers.

-----

The Iowa and Oto are believed to be the first tribal groups to quarry the pipestone. George Catlin also recorded the Sioux, Mandan, Ponca, and Sauk and Fox peoples as being some of the earliest tribes to quarry the pipestone. By the 1700's, the Yankton Sioux had laid claim to the quarries, but the Sisseton-Wahpeton, Santee, and Flandreau also utilized the quarries. Pipestone was traded extensively throughout most of North America. Eastern Dakota tribes traded pipes with western tribes such as the Tetons at the James River Rendezvous, which occurred every year until white intrusion into the area became too powerful.

-----

By the late 1800's, groups of Sioux still came to quarry on a yearly basis. By 1878, pipestone commerce had advanced a great deal. The Flandreau people used pipestone articles for small loans and even boarded trains to sell souvenirs to the passengers. In 1911, the tradition of large groups coming to quarry the pipestone came to an end. Although individual people and smaller groups would continue to quarry the stone even to this day, it was a group of Yankton Elders led by Hollow Horn that became the last large group of Native Americans to visit the quarries and extract the stone.

-----

Joe Taylor, a Mdewakanton Sioux, was probably the most active quarrier in the area until around 1933. Taylor, as well as others who would follow him, quarried in small family groups. James Balmer, the superintendent of the nearby Indian school, administered the quarrying operation until 1937 when the National Park Service took over. The number of quarriers declined drastically during WWII. Albert Drysdale, the park custodian, issued the first quarrying permit in 1946 with one major stipulation: any pipestone quarried had to be used for making pipes and other articles associated with Indian folklore. Interest in quarrying remained at a low level into the early 1950's with no more than four permits issued for any given year.

-----

Three local Chippewa and Sioux families - the Bryans, Derbys, and Taylors - kept the craft of pipe-making alive during the 1950's. For the most part, these crafters learned to carve from their ancestors as the skill was passed from generation to generation. Up until the mid-1960's, the pipestone quarries were worked by a small group of men who used the same quarry pits each year. The number of quarriers, however, jumped from ten to twenty-three between 1966 and 1973 as more Native American families from regional reservations began to develop an interest in pipestone.

-----

Stone pipes have been in use on the North American continent for thousands of years and as previously mentioned archaeological evidence suggests that the pipestone quarries of Pipestone National Monument have been in use for over 3,000 years. Carvers prize this durable yet relatively soft stone, which ranges in color from mottled pink to brick red. Though these grounds are not the only source of pipestone on the North American continent, this location became the preferred source of pipestone among the Plains people because of the quality of the stone. This site was used by many tribes, and tradition states that when people came here - even enemies - they laid down their weapons before quarrying side by side. By 1700, the Dakota Sioux were the dominant presence at the pipestone quarries.

-----

Ceremonial smoking marked the activities of the Plains people: making peace, rallying forces for warfare, trading goods, rituals, and many other ceremonies. Bowls, stems, and tobacco were stored in animal-skin pouches or in bundles with other sacred objects. Pipes were often valued possessions buried with the dead.

-----

There were as many variations in pipe design as there were carvers. By the time George Catlin arrived to the pipestone quarries in 1836, the simple tubes of earlier times had developed into elbow and disk forms, as well as elaborate animal and human effigies. Pipes became widely known as "peace pipes" among European Americans who encountered their customary use at treaty ceremonies, even though pipes have many other very important uses.

-----

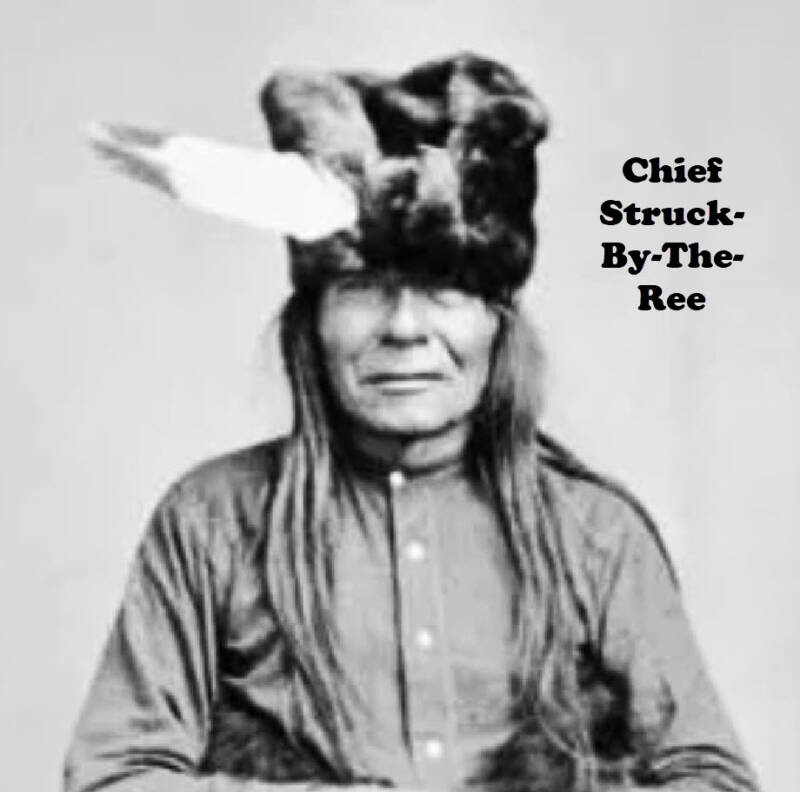

In the mid-19th century, as the Indigenous people of Minnesota were forced onto reservations, some Tribal Nations ceded land that included the pipestone quarry without the consent of the Ihanktonwan Oyate (Yankton Dakota) who controlled it. Ihanktonwan leader Struck By The Ree refused to move his people to a reservation unless they were guaranteed "free and unrestricted access" to the pipestone quarries. The federal government agreed, and the 1858 treaty established a one-square-mile reservation around the quarries.

-----

The Ihanktonwan Oyate held the pipestone quarries and traveled to them in order to procure the pipestone. Within 20 years, newly arrived settlers began digging new quarry pits and stealing the sacred stone. A homestead patent was filed within the quarry reserve area, and the Mayor of Pipestone violated the law for many years by building his house within the reservation and occupying it until the U.S. Army forced him to move out of the reservation. In the 1880s, the Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and Northern Railroad paid the Ihanktonwan for right-of-way through part of the quarry reserve just above the quartzite cliffs. In 1892, a bill passed Congress to establish the Pipestone Indian Boarding School on the northeastern corner of the quarry reservation, despite protests from the Ihanktonwan Oyate. In 1899, they began proceedings to be compensated for damages to their quarry reservation.

-----

After several attempts to reach a resolution first through the U.S. Congress, then through a new agency called the Indian Court of Claims, the Ihanktonwan Oyate spent decades seeking compensation. After the Indian Court of Claims first found that they did not have authority to act on the case, changes in the law later allowed the ICC to rule in the case. The ICC eventually decided against the Ihanktonwan Oyate in 1926, stating that the quarry reservation was only an easement and that they had no right to compensation. The case proceeded to the Supreme Court in 1926. The Supreme Court reversed the ICC's ruling, stating that the federal governments actions at amounted to illegal seizure, and ordered the ICC to determine the value of the land for payment of damages. In 1928, the Ihanktonwan Oyate received $338,558.90 for the land, but lost their claim to the quarries as the title to the land fell under full control of the federal government.

-----

Pipestone National Monument was signed into existence in 1937 and is mandated to protect the right of Native Americans enrolled in any federally-recognized tribe to quarry pipestone.

-----

The cultures of the Great Plains have undergone radical changes since the era of the free-ranging buffalo herds, yet pipe carving is by no means a lost art. Carvings today are appreciated as works of art as well as for ceremonial use. An age-old tradition continues in the modern world, ever changing yet firmly rooted in the past.

Create Your Own Website With Webador